In interviews with Al Jazeera, Kosovo’s president and Bosnia’s defence minister share their concerns about regional security and Moscow-friendly Serbia.

As Russia’s influence grows in the Western Balkans and war rages in Ukraine, the leaders of Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina have said joining NATO would help preserve regional security.

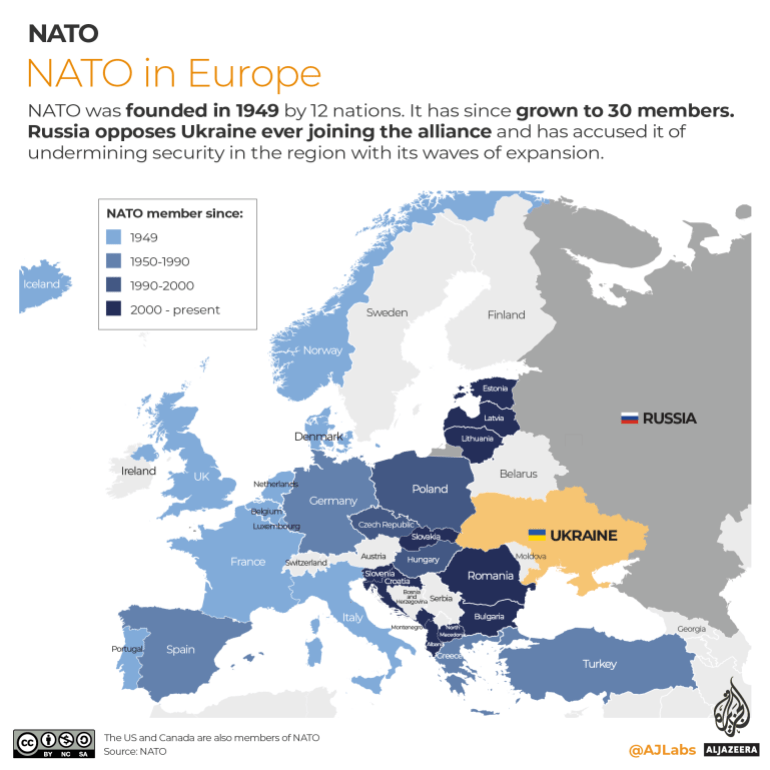

Since February 24, when President Vladimir Putin launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine citing Russia’s opposition to Ukraine’s potential NATO membership as a leading concern, fears have simmered that the crisis may spread to the Western Balkans.

Russia’s alleged moves in the Western Balkans have been documented over the years and include attempts at facilitating coups in Montenegro and North Macedonia before their NATO membership in 2017 and 2020, respectively.

For Bosnia and Kosovo, having experienced mass killings committed by Serb forces in the 1990s under the administration of then Serbian President Slobodan Milosevic, both countries have made it a strategic goal to join the United States-led transatlantic military alliance.

The pair remain the last non-NATO members in the region, aside from Serbia which views NATO as its “enemy”.

In 1999, NATO conducted a 78-day war against Serbia with the stated aim of preventing genocide in Kosovo against ethnic Albanians.

Bosnia is currently participating in the Membership Action Plan (MAP), seen as “the last step before gaining [NATO] membership”, according to Bosnia’s Defence Minister Sifet Podzic.

But as with Kyiv, Moscow has protested against Sarajevo’s NATO bid, despite the 2,400km (1,500 miles) distance between them.

The Russian embassy in Sarajevo warned last year that Russia “will have to react to this hostile act” if Bosnia takes steps towards membership.

Russian ambassador to Bosnia Igor Kalabukhov reiterated this message last month in an interview to Bosnian TV, using Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine as an example.

“If [Bosnia] chooses to be a member of anything, that is its internal business. But there is another thing, our reaction,” he said. “We have shown what we expect on the example of Ukraine. If there are threats, we will react.”

For Kosovo President Vjosa Osmani, Kalabukhov’s warning shows “that Russia has a destructive interest in our region”.

“They especially have an interest in attacking Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and to some extent also [NATO member] Montenegro,” Osmani told Al Jazeera.

Serbia, seen as a Russian proxy, may act with Moscow while feeling “emboldened by what is happening in the continent of Europe right now”, she said.

“The influence that Russia has in Serbia is not downsizing, it’s actually been growing throughout the years.”

‘Indispensable’ membership

Three days after Russia invaded Ukraine, Kosovo requested accelerated membership in NATO and demanded a permanent US military base on its territory.

Osmani has since asked US President Joe Biden to use Washington’s influence to help the country join.

But four NATO members – Spain, Slovakia, Greece and Romania – are yet to recognise Kosovo’s 2008 independence from Serbia, complicating its bid.

Osmani said Kosovo first aims to join mechanisms such as the Partnership for Peace, a NATO programme that encourages cooperation with non-member countries.

“We are already talking to [NATO] members to make sure that everyone understands how membership is becoming indispensable, especially in light of events in Ukraine,” Osmani said, stressing political dialogue.

Podzic hopes that when the Ukraine war ends, geopolitical relations will change and the importance of regional security will increase, possibly leading to fast-tracking Bosnia’s NATO membership.

“But if we wait to fulfil all criteria, unfortunately, it will take a while [to gain membership], because we aren’t investing in security agencies, in military capacities. We will need a lot of time to modernise our army, to buy modern weapons,” Podzic said.

Bosnia stopped investing in its military since about 2010 due to a lack of internal cohesion and obstacles stemming from the 1995 Dayton peace agreement, which was created with the goal of merely stopping the war, he said.

Either way, Russia “won’t be deciding on this”, Podzic said. “[Bosnians] will decide about our path in the military alliance.”

Meanwhile, neighbouring Serbia’s defence budget last year almost doubled from 2018 to about $1.5bn.

Serbia

Serbia, long considered by Brussels as a frontrunner for European Union membership, is the only country in Europe, aside from Belarus, that has not issued economic sanctions against Russia.

Instead, the government and the opposition have shown solidarity with Putin.

As EU countries cancelled flights to Russia, Air Serbia doubled its flights between Belgrade and Moscow last month, only to cancel the decision a day later following backlash.

Moscow and Belgrade have regularly shown close ties.

On February 19, Serbian President Aleksandar Vucic, a populist who this month won a landslide election victory, said on Tanjug state TV that he would meet Russia’s top security official Nikolai Patrushev in Belgrade to discuss Moscow’s claims that “mercenaries” from Kosovo, Albania and Bosnia were being sent to fight on the Ukrainian side.

Officials from Kosovo, Albania and Bosnia had rejected the claims made by Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov.

But later that month, with new sanctions in place and with countries in Europe banning Russian planes from its airspace, Patrushev was reportedly unable to land in Belgrade.

Osmani said the claim of pro-Ukrainian mercenaries is “another part of their propaganda”.

“No matter the facts, some in the EU continue to push for an active appeasement policy towards Vucic, which I believe is a big mistake,” Osmani said.

“We are still waiting, the people of Kosovo, to hear clear messages from the international community towards Serbia that they cannot sit on two chairs at once, especially when these two chairs are very much far away from one another. Unfortunately, we haven’t heard that clear language yet.”

She added that instead of encouraging countries that are fully aligned with the EU and NATO and their values, leaders such as Vucic and the Bosnian Serb secessionist leader Milorad Dodik, “who actually do everything that is the exact opposite of EU values”, are encouraged.